1950–1969: Priest and Philosopher

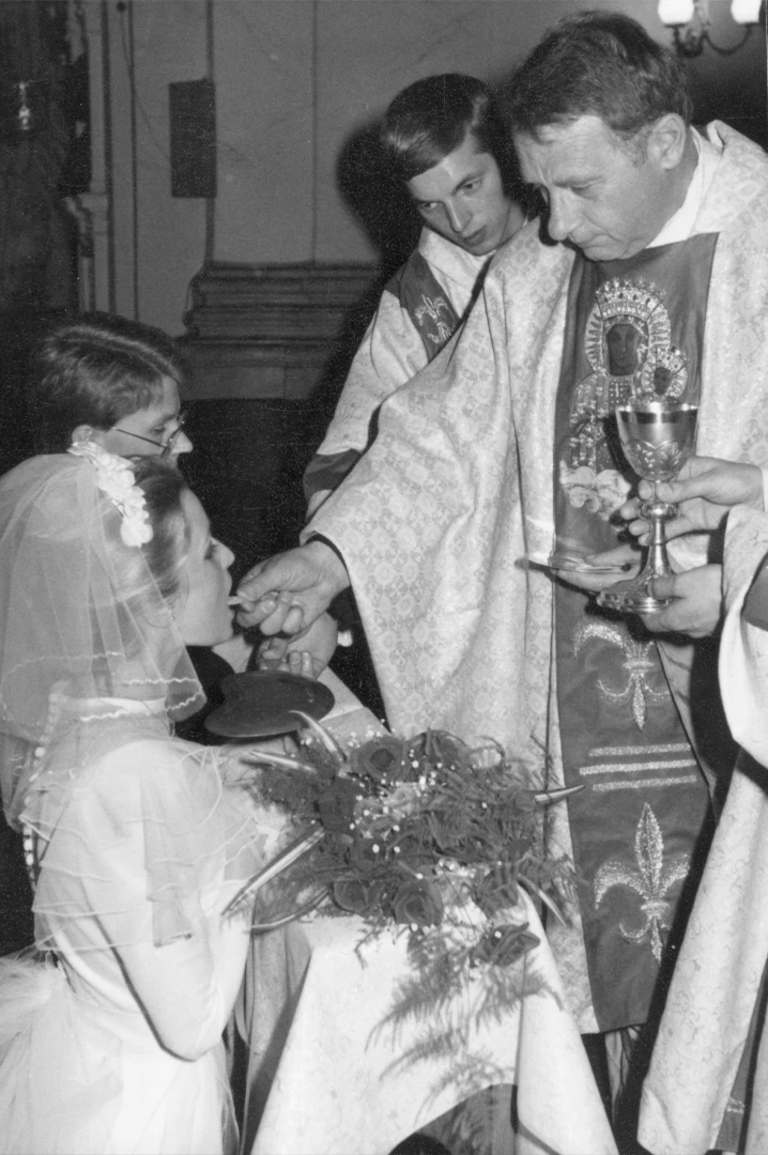

His formation took place during a time of repression against the Church. His model of priesthood was Fr Jan Pietraszko – later a bishop. In his final year at the seminary, he attended lectures on social ethics delivered by Fr Dr Karol Wojtyła. He was ordained on 26 June 1955 at Wawel Cathedral.

Years later, Fr Tischner said of Bishop Pietraszko:

“One could say that my entire philosophy revolves around the idea of religion proposed by Pietraszko. [...] He delved deeply into Polish religiosity. He saw no need to engage in politics and was highly pessimistic about all the revolutionary movements. But he was also somewhat sceptical towards Cardinal Wyszynski, believing that his concept lacked sufficient religious depth.”

Encouraged by Fr Prof. Kazimierz Kłósak, he undertook philosophical studies from 1955 to 1957 at the Faculty of Christian Philosophy at the Academy of Catholic Theology (ATK) in Warsaw. He then continued his studies from 1957 to 1959 at the Jagiellonian University, where he explored the philosophy of Edmund Husserl under the supervision of Prof. Roman Ingarden.

From 1957 to 1963, he served as a vicar and catechist – first in Chrzanów, then at the parish of St Casimir in Kraków. In 1963, he defended his doctoral thesis under Ingarden’s supervision. From that point on, he taught philosophy at the Major Seminary, and later at the Pontifical Faculty of Theology (from 1981, the Pontifical Academy of Theology).

In 1968, he travelled to the West for the first time. He began with a short language course in Vienna and then on a scholarship, conducted research at the Husserl Archives in Leuven. There, he became acquainted with the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas and Paul Ricoeur.

In the mid-1960s, he began contributing to Tygodnik Powszechny and the monthly Znak. In 1965, he moved into the residence for priest-professors at 10 Św. Marka Street in Kraków.

1970–1979: Thinker and Pastor

The 1970s were a time of particularly intense pastoral and academic activity for Fr Tischner. His approach stood out for its intellectual courage and openness to dialogue.

At St Mark’s Church in Kraków, he celebrated children’s Masses, introducing dialogue-based homilies – something unheard of at the time. He even allowed the little ones to bring their favourite cuddly toys to the altar. He believed that children should be listened to and given space within the Church.

Tischner fondly recalled these sermons for the youngest, especially one conversation about the Eucharist:

“I asked the children where bread and wine come from. They knew a bit about bread, but wine was more difficult. However, one little girl had just returned from Italy, where she’d seen vineyards being cultivated. [...] When I later asked the children why Jesus comes to us through wine and bread, one boy replied: ‘Because there’s enchanted human labour in them’. I sat down in astonishment. I later expanded on this during the first Solidarity congress”.

At St Anne’s Church, he led the famous “Thirteens” – Masses that gathered Kraków’s intellectuals, during which he tackled contemporary and difficult themes at the intersection of faith, ethics, and culture. In his sermons, he often reminded listeners – as he later put it –

“Piety is very important, but it’s no substitute for reason”.

He collaborated with many circles – doctors, artists, scholars. He had a special bond with the renowned psychiatrist Antoni Kępiński. Their friendship deepened his sensitivity to the themes of hope and despair as the two poles of human existence. In 1974, he earned his postdoctoral degree (habilitation) at the Academy of Catholic Theology with a thesis titled Phenomenology of Ego-Consciousness. In his writings, he boldly criticised the dominant Thomistic current in the Church, which he believed evaded the anxieties of modern humanity by retreating into the safe confines of ahistorical philosophy. His widely discussed essay The Decline of Thomistic Christianity sparked a wave of debate known as the “Dispute with Thomism”.

Tischner was unafraid of polemics, but always sought understanding. His thinking remained close to people – deeply Christian, yet bold and modern at the same time. In 1975, his first book was published: The World of Human Hope, in which he outlined his vision of the human being as one who seeks meaning, hope, and freedom. In the latter half of the decade, he worked on The Polish Shape of Dialogue (1979) – an attempt to describe the relationship between Christianity and Marxism, which, in the reality of the People’s Republic of Poland, stood in open conflict.

At the same time, he became involved in the activities of independent cultural groups, including the so-called “Flying University” – an educational initiative operating outside the official system. Tischner’s voice became increasingly recognisable, as he combined philosophy with priesthood, spirituality with culture, and words with action.

1970–1989: Riding the Wave of “Solidarity”

In the 1980s, Fr Tischner became one of Poland’s most respected intellectuals. From the very beginning, he was involved with the “Solidarity” movement, playing a unique role as a priest, thinker, and publicist. On 19 October 1980, at the invitation of the newly established trade union, he delivered a moving homily in Wawel Cathedral entitled Solidarity of Consciences. This sermon – a call for spiritual awakening and collective responsibility – later formed the foundation of his book The Ethics of Solidarity (1981). In it, he wrote:

“What does it mean to be in solidarity? It means to carry another’s burden. [...] Solidarity, the one born from the pages and spirit of the Gospel, does not need an enemy or opponent to grow and thrive. It addresses everyone, not against anyone”.

On 5 October 1981, during the First National Congress of NSZZ “Solidarity” held at the “Olivia” Sports Hall in Gdańsk, he gave a speech in which he expanded on the idea of solidarity as openness to dialogue:

“We must leave here with enlarged souls. Whoever still harbours a spectre in their spirit, let them cast it out. We must enlarge the soul. [...] And as you leave here, dear brothers, do not forget to shake the hand of your opponent. It is through such gestures that the

spirit of the Republic is born”.

His words resonated with workers, students, and opposition activists, gaining a near-manifesto status within the Solidarity movement. A backstage anecdote from the Congress tells of Lech Wałęsa being asked whether The Ethics of Solidarity was a good book. He supposedly replied, “It’s good, but if only the priest had taken a real jab at the communists…” According to other sources, Wałęsa is said to have remarked: “I haven’t read it, but you can still learn something even from the dumbest book”, to which Tischner, with characteristic humour, responded: “And that consoled me greatly”.

Tischner energised rural communities connected to “Solidarity”. He organised aid for the Podhale region – supporting local activists, helping to import agricultural machinery from Austria, and arranging placements for young people in agricultural schools. Beginning in 1981, he initiated the tradition of August Masses for the Homeland on Mount Turbacz – an annual pilgrimage that drew hundreds from across Poland.

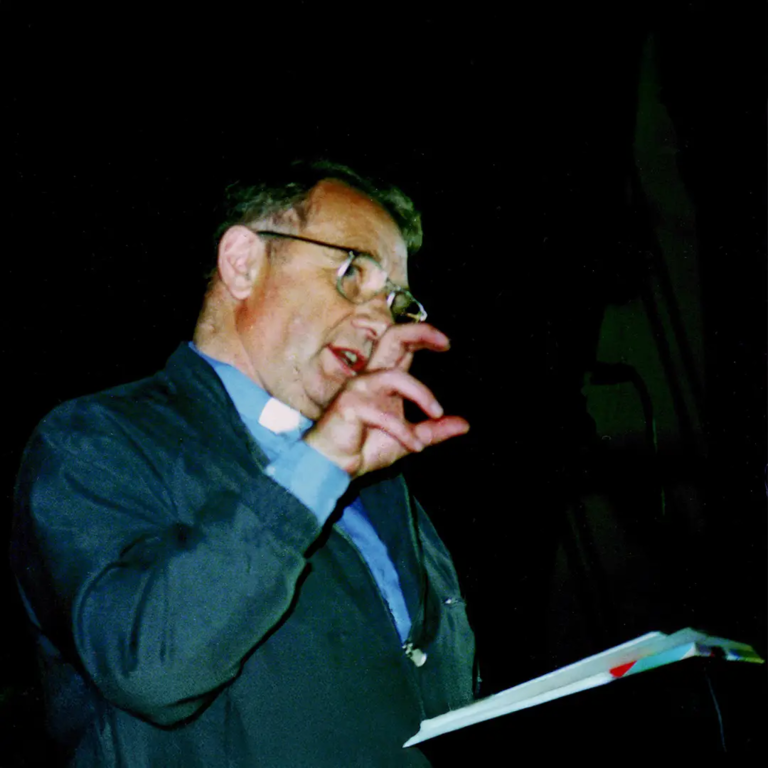

State Higher School of Theatre in Kraków, and also lectured in philosophy at the Jagiellonian University. His Tuesday evening monographic lectures at Collegium Witkowski (6:00 p.m.) were open to all and drew crowds of students as well as Kraków residents captivated by his personality.

In 1981, together with Hans-Georg Gadamer and Krzysztof Michalski, he co-founded the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna. This research institution – created to build intellectual bridges between East and West during the Cold War – played a significant role in the emancipation of the cultural achievements of Central Europe.

“He was a true good spirit – the daimonion – of that place. I think it was there that I most strongly experienced his extraordinary gift: his ability to transform and illuminate the space he entered. I saw people’s faces light up in his presence, whether it was the face of a professor or a porter”. – recalled the philosopher Cezary Wodziński.

In 1983, as part of IWM’s initiatives, the first in a series of meetings between Pope John Paul II and intellectuals from around the world took place at Castel Gandolfo. There, Tischner met Emmanuel Lévinas.

In 1985, Fr Tischner was awarded the title of associate professor at the Pontifical Academy of Theology, where he served as Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy. He later declined an offer to become Rector, preferring to devote himself fully to academic and pastoral work.

1990–1999: A Man of Hope and Dialogue

The 1990s were a time of great popularity and widespread recognition for Fr Tischner – both as a thinker and as a moral authority. Although he consistently avoided direct involvement in day-to-day politics, his voice was clearly heard in the most important public debates of a resurgent Poland.

He was valued not only for his insights into the social and political transformations occuring in Poland and beyond, but also for his cultural discernment – evidenced by his appointment to the jury of the Polish Feature Film Festival in Gdynia (1992).

In 1990, he published The Philosophy of Drama – a work that marked the culmination of his philosophical pursuits up to that point. In the following years, he authored numerous influential essays and books, including The Unhappy Gift of Freedom (1993), Confession of a Revolutionary (1993), In the Land of Diseased Imagination (1997), and The Wayward Priest (1999).

He also co-authored several widely read volumes of conversations: Between the Lord and the Priest (1995, with Adam Michnik and Jacek Żakowski), Tischner Reads the Catechism (1996), Persuading God (1999), and The Meeting: Anna Karoń Ostrowska in Conversation with Fr Józef Tischner (published posthumously in 2003). The greatest phenomenon, however, proved to be The Highlander’s History of Philosophy (1997) – a series of witty and humorous philosophical tales written in a stylised Podhale dialect.

During this period, Tischner also gained broad public recognition through his media activity. He appeared regularly on TV Katowice, where Ewelina Puczek filmed a series of interviews with him between 1994 and 1997. On national television, he featured in his own programme Tischner Reads the Catechism, as well as in the series The Seven Deadly Sins – Highlander Style(1995). He also co-hosted radio broadcasts entitled Conversations Without a Punchline (Radio Kraków, with Jarosław Gowin), and his books were read aloud on air.

He received prestigious honours for his writing and contribution to public discourse – including the Jurzykowski Foundation Prize (1987), the Kisiel Award, and the Polish PEN Club Award (1993). He was awarded honorary doctorates by the University of Łódź and the Higher School of Pedagogy in Kraków (now the University of the National Education Commission – UKEN).

1990–1999: Illness and Death

In 1999, President Aleksander Kwaśniewski awarded him the Order of the White Eagle – Poland’s highest state honour, bestowed for outstanding contributions to national culture.

In one of his final interviews, Józef Tischner reflected on the future of faith:

“I am convinced that the true history of Christianity still lies ahead of us, not behind us. Until now, Christianity has been entangled in a political struggle for power. It has been interpreted through the lens of that struggle, and subsequently either accepted or rejected. It would be hard to name a single dogma of faith that hasn't been coloured by political intrigue.

Christianity itself sought its identity by emphasising the differences – even the antagonism – in relation to other faiths. But it seems that this story has come to an end. Christianity, freed from politics and from the need to define itself against other religions, may come to understand itself more deeply through the lens of the hope it offers humanity.

I especially want to emphasise the word hope. There is a time for defining the meaning of faith, and there is a time for building hope”.

Fr Prof. Józef Tischner died on 28 June 2000 in Kraków. He was laid to rest on 2 July at the cemetery in Łopuszna.

1999-1999: Disease record

In the final years of his life, Fr Tischner battled laryngeal cancer. Despite losing his voice, he continued to write until the very end.

“Together with my mum and dad, we moved in with him during those last months, because he was losing his balance and kept falling. After his larynx was removed, he communicated with us using notes, but in the final months his handwriting became illegible. I remember him sitting with his hand to his temple, the grimace on his face revealing relentless headaches.

I see him in all the torment of his body, and yet from it radiated an extraordinary dignity. He endured truly unimaginable suffering, but one could still feel the strength of humanity in him – and perhaps a spark of the divine – that seemed to radiate outward to others. It wasn’t about mystical experiences, but about the courage of being.

That strength was always in him, but during his illness, I saw it in its purest form. Even then, he remained open to people, able to instil hope, somehow lifting the spirits of those who came to visit him”. – recalls his nephew, Łukasz Tischner.